Survey of taro varieties and their use in selected areas of Cambodia

Pheng Buntha, Khieu Borin, T R Preston* and B Ogle**

Center for Livestock and Agriculture

Development

buntha@celagrid.org

*Finca Ecológica, TOSOLY,

Socorro Colombia

**Swedish University of

Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Nutrition &

Management,

PO Box7024, 75007,Uppsala,

Sweden

Abstract

A survey was carried out in two provinces of Pursat and Takeo, representing two of the major Agro-Ecological Zones (AEZs) in Cambodia. Fifty four families from six villages were interviewed. Two varieties of taro, Chouk and Sla, are commonly cultivated and Trav Prey (wild taro) also grows naturally in Pursat and Takeo. Chouk and Sla taro are fast growing, varieties and can be harvested 5-8 months after planting.

Taro is considered to be a good vegetable crop and is planted near the houses in the two selected provinces in the late dry season and early rainy season, between April and July. The tubers are used for human consumption while stems and leaves are not widely used for animal feeding. The main reasons for not using them are the itching they cause, and lack of tradition and knowledge. The average tuber yield is 4.5-6 tonnes ha-1, while the average yield of petiole and leaf is 5-8.5 tonnes ha-1.

Farmers considered stems to be worst with regard to causing itching, followed by leaves and then root. However the effect can be reduced by boiling, frying, ensiling and sun drying. Both salt and sugar palm syrup can be used for ensiling.

Key words: Chouk and Sla taro, itching, leaf, oxalic acid, root, stem

Introduction

There are more than 200 cultivars of taro, selected for their edible corms or cormels, or ornamental plants. These fall into two main groups: Wetland taros, the source of the Polynesian food poi, which is made from the main corm; and upland taros, called "dasheens" in Florida and the West Indies, which produce numerous eddos that are used much like potatoes, as well as a large edible mammy (Florida ID: 899). In Cambodia, taro can be found most parts of the country, particularly along the Tonle Sap Great Lake and Mekong River. Taro can be a potential protein source for animals, especially pigs due to the good nutritional quality of the leaves (DM basis): 25% crude protein (CP), 12.1% crude fibre (CF), 12.4% Ash, 10.7% ether extract (EE), 39.8% nitrogen-free extract (NFE), 1.74% Ca, and 0.58% P (FAO 1993). The level of CP, although slightly higher than that in yam, cassava or sweet potato, contains low amounts of the amino acids histidine, lysine, isoleucine, tryptophan and methionine (AFRIS 2004). Leterme et al (2005) reported that Xanthosoma leaf had high amino acid content and a good balance of amino acids.

Takeo province is one of the provinces representative of the Mekong floodplain zone and has high population and potential for crop cultivation. During the raining season, water from the Mekong floods large areas of the province, thus providing the fertilizer, soil and water for crop cultivation, especially rice production. In the dry season, crop cultivation is depending on rainfall. Pursat, located in the northwest of Cambodia, is representative of the Great Lake flood plain. This province has potential, particularly in the rainy season, for supplemental water for rice crops in case of dry spells, and is also important for vegetable production, especially the taro plant, which is commonly grown and used, and needs large amounts of water. So far there are few studies in Cambodia on the different uses of taro, particularly for livestock feeding, and therefore the present study will document the matters related to taro in the two main agro-ecological zones (AEZs) in Cambodia.

Objectives of the survey

-

To document the existing varieties cultivated in the two main AEZs in Cambodia

-

To study cultivation practices of taro, its uses and common methods to reduce the oxalate content

-

To study the use of taro for human and animal food.

Methods and data collection

Development of questionnaire for the survey

A questionnaire was developed by modifying the information were gotten from farmers during farmers discussion to collect qualitative and quantitative data through direct interviews with farmers. Information and data collected indicated the availability of taro varieties, in their natural form or cultivated, and the use of both tubers, leaves and stems for different purposes. The main information and data collected in the survey were:

- Varieties of taro, both wild and cultivated;

- Types of production of taro and fertilization;

- Harvest of leaves and tuber production;

- Seasonality of tubers, leaves and stems;

- Community knowledge about taro and its toxicity;

- Local practices for the reduction of toxicity;

- The use of tubers, leaves and stems for humans and pigs;

- Price of taro tubers, leaves and stems;

- Samples of important varieties were taken for chemical analysis.

Site selection

There are four major agro-ecological zones (AEZs) in Cambodia, and each represents conditions which determine agricultural practices and production systems. However, only two main agro-ecological zones were selected for the survey, due to their high population density, and the fact that most of the people depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. The two ecological zones were:

- Mekong floodplain, with three villages, namely Krom, Sras Takoun and Ta Kouk in Takeo Province; and

- Great Lake floodplain, with three villages, namely Kra Gnao, Chung Rouk and Tasas in Pursat Province.

General profile of the sites

Takeo is located in the southwest of Cambodia and has borders with Kadal, Kompong Spue and Kampot provinces, and Vietnam. The total population is 0.85 million and 85-90% make their living on agricultural cultivation and keeping livestock. Treang is one of the 10 districts selected for the survey. However, due to time limits only Krom, Sras Takoun and Ta Kouk villages were selected. The agricultural land of Sonlong is 2,569 ha. The main livelihood activities are rice production, livestock keeping and fishing.

Pursat has a total population of 0.5 million and 74.1% live in the rural areas. Phnom Kravanh is one of the 6 districts with a total of 53 villages selected for the survey. Howeve,r due to limit of time only 3 villages with access to water were chosen for the survey. The main livelihood activities are rice production and livestock keeping. People also go to the forest in the dry season to collect forest products and by-products.

Field work and data collection

After development, the questionnaires were distributed by team leader to team members to understand them before the actual field work. Team members met with local authorities to officially inform about the study and asked for their advice. At the beginning of the interview team members were allowed to go in pairs to get more experience and be more familiar with the questions. The team members had a meeting every night and the team leaders reviewed the questionnaires daily for correcting the incredible information by feed back with farmer. The sample size is shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Number of families interviewed in each village |

||

|

Province |

Village |

No. of families |

|

Pursat |

Kra Gnao |

9 |

|

Chung Rouk |

9 |

|

|

Tasas |

9 |

|

|

Takeo |

Krom |

9 |

|

Sras Trakun |

9 |

|

|

Ta Kouk |

9 |

|

|

Total |

54 |

|

Data analysis

The qualitative data were given codes to ease the entry of data

into the spreadsheet. Analysis of survey data was by descriptive

statistical analysis using SPSS v. 12.

Results

Rice cultivation

The average family size in the 3 villages in Takeo province is 5.5, similar to average at the national level, while the average family size in the 3 villages in Pursat province is 5.7. In selected villages in Takeo province, farmers cultivate only rice annually in the rainy season, and each family has an average of 2.1 ha of paddy field. The average yield of rice is 0.9 tonnes/ha. Among the families interviewed 96.3% cultivate rice, while 3.7% survive on other activities. In Pursat Province, all interviewees also produced only one rice crop per year in the rainy season and each family owns 4.6 ha of paddy field. Pursat is a less densely-populated area and that is why each farmer owns larger paddy plots than those in Takeo. The average yield of rice in Pursat was 1.3 tonnes/ha (Table 2). The low yield of rice in both selected study areas may be due to problems in the estimation of yield by farmers, as they only estimate the total yield of rice per year. Farmers in Pursat use rice entirely for home consumption, while 38% of interviewed farmers in Takeo use rice for own consumption and 62% produce rice both for sale and own consumption.

|

Table 2. Paddy field, yield and uses of rice in the selected villages in Takeo and Pursat Province |

||||||||

|

Province |

Village |

Produce rice |

Land size, ha |

Total yield, tonnes |

Purpose of use, % |

|||

|

Yes |

No |

Average |

SE |

Average |

Consume |

Sell and consume |

||

|

Takeo |

Krom |

100.0 |

0.0 |

2.3 |

0.40 |

0.9 |

55.6 |

44.4 |

|

Sras trakun |

88.9 |

11.1 |

1.7 |

0.38 |

1.2 |

25.0 |

75.0 |

|

|

Ta kouk |

100.0 |

0.0 |

2.4 |

0.64 |

0.7 |

33.3 |

66.7 |

|

|

Average |

96.3 |

3.7 |

2.1 |

0.50 |

0.9 |

38.0 |

62.0 |

|

|

Pursat |

Kra Gnao |

100.0 |

0.0 |

4.3 |

0.60 |

1.2 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

Chhung rouk |

100.0 |

0.0 |

4.9 |

0.82 |

1.6 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Tasas |

100.0 |

0.0 |

4.6 |

0.50 |

12 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Average |

100.0 |

0.0 |

4.6 |

0.60 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

Taro cultivation

Varieties of taro

Taro is a wetland crop that is cultivated in most regions in Cambodia. There are two kinds of taro, the water taro and land taro. In this study it was found that although two varieties are available in the selected villages only water taro is preferred for cultivation by farmers, and the other variety is grown in canals and lake sides near the houses.

Trav Chouk (Chouk taro) (Photo 1) is the water taro and it can grow very well in water, but also can grow in muddy and even in dry land. It is 0.6-1m high, with the high depending on management and fertilizer application. The root is sweet with a weight of 0.5-1kg, and varies with the cultivation practices. The stem is white in color and the leaves green, and it is sometimes called Trav Chen (Chinese taro). It is cultivated nearby the house in small streams as well as in canals. This practice allows farmers to easily harvest the petiole for cooking. This kind of taro can be harvested 6-8 months after planting.

Sla taro (Photo 2) is land taro that can grow with little water but can not grow in deep water. Normally it is planted for tuber production. However, stems from this variety are rarely cooked as vegetables for humans, but are fed to pigs after cooking. The height of the plant and weight of root are quite similar to Chouk taro. The characteristic which identifies Sla taro is the violet color of the stem, especially the middle leaf. Sla taro can be harvested within 5-7 months after planting.

Trav Prey (Wild taro) (Photo 3) grows naturally and can be found in forests, ponds, streams and canals. The plant is from 0.6 to more than 1 m high, depending on the soil fertility. This variety can also grow on land or mud. Farmers mentioned that they have used petiole from this variety for pig feeding after cooking, but never use it for human food as they believe that it is poisonous and causes itching.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Farmers in Takeo preferred Chouk taro, while farmers in Pursat use both varieties. The reason that farmers in Takeo preferred Chouk taro is because they can use it for human food (Table 3) and it can grow well even in flooded areas.

|

Table 3. Percentage planting Chouk and Sla taro |

||

|

Village |

Chouk, % |

Sla, % |

|

Krom |

100.0 |

0.0 |

|

Sras trakun |

66.7 |

33.3 |

|

Ta kouk |

77.8 |

22.2 |

|

Kra Gnao |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

Chhung rouk |

55.6 |

44.4 |

|

Tasas |

100.0 |

0.0 |

|

Average |

66.7 |

33.3 |

Chemical composition of Chouk and Sla taro

The chemical composition of Chouk and Sla taro is quite similar in DM and CP (Table 4). However, during the study, due to lack of analytical facilities, taro samples were not analysed for calcium oxalate. Farmers mentioned that in their experience Chouk and Sla taro have similar poisonous characteristics (itching).

|

Table 4. Chemical composition of Chouk and Sla taro |

||||||

|

|

Chouk taro |

Sla taro |

||||

|

Root, % |

Petiole, % |

Leaf, % |

Root, % |

Petiole, % |

Leaf, % |

|

|

DM |

31.4 |

6.3 |

19.1 |

31.0 |

7.4 |

18.1 |

|

CP |

10.2 |

14.9 |

26.3 |

10.2 |

15.9 |

27.8 |

Purposes for cultivation of taro

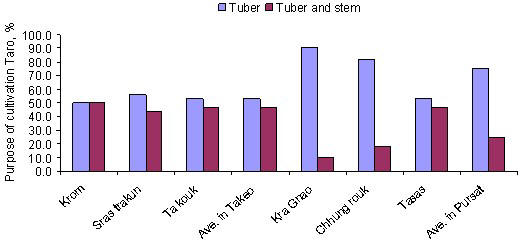

The main purpose of planting taro is root and petiole production for family consumption. In Pursat most interviewed farmers cultivated taro for both tuber and petiole production while 47% and 53% of the farmers in Takeo Province planted taro for tuber-petioles and tuber, respectively (Figure 1).

|

|

| Figure 1. Percentage of farmers in the different villages cultivating taro for tubers or for tubers+stems |

Reasons given for cultivating Chouk taro

Sixty one percent of interviewed farmers selected Chouk taro for cultivation because it is easy to plant (Figure 2). The selected sites for the survey are generally wet and muddy in the rainy season, and Chouk taro can easily survive in these conditions.

|

|

|

|

Reasons given for cultivating Sla taro

The Sla taro is planted as a root vegetable for human consumption. It is generally planted in association with other crops. Those interviewed mainly chose Sla taro because of its high yield (Figure 3).

|

|

|

|

Experience of taro cultivation

Most farmers have planted taro for many years, but a few have started only a few years ago (Figure 4). Generally the farmers have a good knowledge about the management and fertilizing of the taro crop.

|

|

|

|

Taro seed bank

The farmers always keep the small tubers (corm) for the next growing season, and the techniques for storing the tubers vary from farmer to farmer according to their experience. Around 54 % of farmers keep the small tubers under their house under a layer of rice straw for the next season's planting. An alternative technique is to keep the roots in the field so that they can germinate after the first rain of the season. Another method involves placing the tubers near a water source in sandy soil (Table 5).

|

Table 5. Storing taro roots as planting material |

||||||

|

Village |

Keep root in field |

Keep root near house |

Keep root near water source |

Keep root under house |

Keep root in sandy soil |

No |

|

Krom |

66.7 |

22.2 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Sras trakun |

33.3 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

33.3 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

|

Ta kouk |

44.4 |

0.0 |

11.1 |

22.2 |

0.0 |

22.2 |

|

Kra Gnao |

0.0 |

0.0 |

11.1 |

77.8 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

|

Chhung rouk |

11.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

88.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Tasas |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Average |

25.9 |

5.6 |

7.4 |

53.7 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

Seeds for planting

Two common methods that farmers are using are direct and indirect planting. For the direct method, farmers plant tuber seeds directly in the field and the indirect method involves taking the tubers to a nursery and then transplanting the young plant in the plots. Most farmers (89%) preferred indirect planting, as the survival rate is much higher, while 11% of the farmers practiced direct planting because it requires less labour (Figure 5).

|

|

|

|

Soil preparation and planting

The soil is generally plowed twice then harrowed once. After the first plowing, fertilizer is applied and the ploughed soil left to sun-dry for one week before the second ploughing. Cultivation starts in the late dry season and early rainy season, during April to July. The small plants from the nursery at an age of 15 days are planted with a distance of 40-54cm (Figure 6) between rows. The tuber should be completely covered and water supplied at this stage. However, the distance between rows can be smaller or bigger according to the variety of the taro and experience of farmers in their location.

|

|

|

|

Management and fertilization

Taro cannot grow fast unless water supply is optimum, because taro needs a lot of water. One month after planting, the farmers pump water to swamp the taro field so that the soil is always wet. During the first 2-3 months, farmers water 2 or 3 times per day. Fertilizer is used during the soil preparation, and more is applied after planting. The use of fertilizer was dependent on the soil fertility and the management. In Takeo Province 48% of the farmers applied fertilizers and the 52% who did not believe that as taro is planted in low-lying soils or on the bottom of canals or ponds, organic materials are available to plants through rain wash. In Pursat 67% of farmers used fertilizer in order to increase yields (Table 6). Beside watering and fertilizing, taro was weeded and the soil around the plant loosened at the age of 1.5 months.

|

Table 6. Percentage of farmers using fertilizer, and kind of fertilizer applied for taro cultivation |

||||||||

|

Apply

fertilizer, |

Takeo |

Pursat |

||||||

|

Krom |

Sras trakun |

Ta kouk |

Mean |

Kra Gnao |

Chhung rouk |

Tasas |

Mean |

|

|

Yes |

44.4 |

55.6 |

44.4 |

48.1 |

66.7 |

77.8 |

55.6 |

66.7 |

|

No |

55.6 |

44.4 |

55.6 |

51.9 |

33.3 |

22.2 |

44.4 |

33.3 |

|

Fertilizers, % |

||||||||

|

Organic |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

16.7 |

57.1 |

100.0 |

57.9 |

|

Chemical |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Both |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

83.3 |

42.9 |

0.0 |

42.1 |

|

Amount of fertilizer, tonnes/ha (SE) |

||||||||

|

Organic |

1.96 (0.52) |

9.98 |

1.67 (1.07) |

4.54 (2.47) |

1.38 |

1.10 |

4.6 |

2.66 (0.68) |

|

Chemical |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

2.05 |

5.98 |

0.0 |

2.68 (0.09) |

Harvesting

Taro is harvested between December and January. The tuber yield was different between locations due to the different management and fertilization practices. The average tuber yield was 4.5-6 tonnes ha-1 for all interviewed sites (Figure 7). The average of petiole and leaf reported by interviewed farmers was 5-8.5 tonnes ha-1 (Figure 7).

|

|

|

|

The price of root was 600 - 1000 Riel (0.15-0.25 $) per kg depending on the quality of the tubers and season (Table 7). The petioles are rarely sold, but the price is around 100-200 Riel (0.025-0.049$) per kg. Generally, leaves are thrown away or sometimes fed to pigs, and on a few occasions sold at a price of 100 Riel per kg.

Uses of taro for humans and animals

The tubers of taro are used for human food, particularly during the period when there is a shortage of rice, and they are not generally used as animal feed (Table8). However, some farmers do feed poor quality tubers to pigs. Leaves have been used for human food and feeding to pigs, but are never used for poultry. Furthermore, petioles are fed to pigs after boiling with broken rice or rice bran, but are also discarded at harvesting time. Some farmers use the tubers as a vegetable by cooking with fish or snail to produce a soup.

|

Table 8. Different uses of taro for humans and animals, % of households |

||||||||

|

|

Takeo |

Pursat |

||||||

|

Krom |

Sras trakun |

Ta kouk |

Mean |

Kra Gnao |

Chhung rouk |

Tasas |

Mean |

|

|

Use of taro tuber, % of households |

||||||||

|

For human food |

100.0 |

88.9 |

100.0 |

96.3 |

100.0 |

77.8 |

88.9 |

88.9 |

|

For human food and pig feed |

0.0 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

3.70 |

0.0 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

7.4 |

|

For human food and poultry feed |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.00 |

0.0 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

3.7 |

|

Waste products |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.00 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

The use of taro leaf, % of households |

||||||||

|

For human food |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.00 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

For human food and pig feed |

0.0 |

0.0 |

22.2 |

7.41 |

11.1 |

55.6 |

100.0 |

55.6 |

|

For human food and poultry feed |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.00 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Waste products |

100.0 |

100.0 |

77.8 |

92.6 |

88.9 |

44.4 |

0.0 |

44.4 |

|

Use of taro stem, % of households |

||||||||

|

For human food |

88.9 |

55.6 |

44.4 |

62.9 |

55.6 |

33.3 |

0.0 |

29.6 |

|

For human food and pig feed |

11.1 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

25.9 |

33.3 |

66.7 |

100.0 |

66.7 |

|

For human food and poultry feed |

0.0 |

0.0 |

11.1 |

3.70 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Waste products |

0.0 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

7.41 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

3.70 |

Twenty two % of the interviewed farmers in Takeo fed taro to their pigs while 78% did not use it. In Pursat 63 % used taro for their pigs while 37% did not use it. This could indicate that taro has been used for pigs for generations, although there is no data to show the potential or benefit of feeding taro to growing pigs. Interviewed farmers reported on their experiences of using taro for pigs; one observation reported was that their pigs prefer taro after boiling with rice bran or broken rice and they also commented on the availability of taro on their farms. Generally the farmers believe that taro has good nutrient properties for animals and also can reduce the amount of broken rice or rice bran in pig diets.

Reasons for not using taro stems and leaves for pig feed

Most of the interviewed farmers did not use taro petiole and leaf for their pigs (Table 9).

|

Table 9. Percentage of farmers that use taro for pigs, and their reasons |

||||||||

|

|

Takeo |

Pursat |

||||||

|

Krom |

Sras Trakun |

Ta kouk |

Mean |

Kra Gnao |

Chhung rouk |

Tasas |

Mean |

|

|

Yes |

11.1 |

33.3 |

22.2 |

22.2 |

22.2 |

66.7 |

100.0 |

63.0 |

|

No |

88.9 |

66.7 |

77.8 |

77.8 |

77.8 |

33.3 |

0.0 |

37.0 |

|

Reasons for using taro for pigs, % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Pigs like it |

100.0 |

0.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

16.7 |

|

Household habit |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Own production |

0.0 |

33.3 |

50.0 |

27.8 |

0.0 |

16.7 |

0.0 |

5.6 |

|

Easy to feed |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Available |

0.0 |

66.7 |

0.0 |

22.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

55.6 |

18.5 |

|

Good performance |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

33.3 |

11.1 |

|

Supply good nutrients |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

66.7 |

11.1 |

25.9 |

|

Reduces use of rice |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

16.7 |

0.0 |

5.6 |

|

Can eat |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

50.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

16.7 |

The reasons given were that they cause itching (31%), lack of knowledge (30.5%) and that they had never tried them (20.7 %) (Table 10). The use of taro for pigs is not widespread because farmers lack the knowledge for the use and processing of taro and the potential benefits of feeding it to pigs.

|

Table 10. Reasons given for not using taro for pigs, % of farmers |

||||

|

Village |

Itching |

Never used |

Lack of knowledge |

Never used + lack of knowledge |

|

Krom |

0.0 |

37.5 |

25.0 |

37.5 |

|

Sras trakun |

44.4 |

11.1 |

33.3 |

11.1 |

|

Ta Kouk |

0.0 |

0.0 |

62.5 |

37.5 |

|

Kra Gnao |

22.2 |

55.6 |

22.2 |

0.0 |

|

Chhung Rouk |

20.0 |

20.0 |

40.0 |

20.0 |

|

Tasas |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Mean |

31.1 |

20.7 |

30.5 |

17.7 |

Problems of oxalate and itching in taro

In practice, some farmers feed taro to their pigs after boiling with broken rice. Sometimes they observed that pigs still have a problem with itching, but not as much as when consuming the fresh material. Around 44.4 % of farmers thought that there was no danger with feeding taro, while 55.6 % observed that their pigs seemed to have itching, but this did not affect their health. It may be that there are lower intakes when pigs seem to suffer from itching.

The whole taro plant contains oxalic acid that can result in itching, but the amount may depend on the parts of the plant, and 77.4 % of the interviewed farmers mentioned that the petioles have highest potential to cause itching, followed by the leaves and then the tubers (Table 11). However, their assessment was based on their previous experience of holding different parts of the plant.

|

Table 11. Farmers assessment of the severity of itching caused by the different parts of the plant, % |

|||||

|

Village |

Don’t know |

Root |

Stem |

Leaves |

Same |

|

Krom |

22.2 |

0.0 |

77.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Sras trakun |

0.0 |

0.0 |

88.9 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

|

Ta kouk |

37.5 |

0.0 |

62.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Kra Gnao |

0.0 |

11.1 |

88.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Chhung rouk |

0.0 |

0.0 |

88.9 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

|

Tasas |

0.0 |

0.0 |

55.6 |

33.3 |

11.1 |

|

Mean |

9.4 |

1.9 |

77.4 |

9.4 |

1.9 |

Local methods for reducing oxalate or itching

As many as 96% the interviewed farmers boiled taro before feeding it to their pigs. Seventeen % of the farmers used sugar palm syrup to reduce itching after boiling, while 2% used salt, frying or sun drying. (Table 12). The most common method to reduce the oxalate or itching is thus boiling, but this takes time and firewood.

|

Table 12. Local method and experiences of reducing oxalate in taro |

||||||

|

Village |

Boiling |

Ensiling |

Frying |

Using salt |

Using palm syrup |

Sun-drying |

|

Krom |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Sras trakun |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Ta kouk |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Kra Gnao |

100.0 |

11.1 |

0 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

|

Chhung rouk |

75.0 |

0.0 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

33.3 |

0.0 |

|

Tasas |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

55.6 |

11.1 |

|

Mean |

96.2 |

1.9 |

1,9 |

1.9 |

16.7 |

1.9 |

Locally available resources for pigs

In Cambodia, farmers in rural areas raise pigs as a source of savings and for ceremonial purposes. Pigs are fed on rice bran, broken rice, kitchen waste, water spinach, water hyacinth and some vegetables. However, some farmers used concentrate feed as supplement. Almost all (90.8%) of the interviewed farmers use rice bran as basal feed for their pigs, 50% fed kitchen waste and 72% fed water spinach as supplement (Table 13). However few farmers used concentrate for their pig due to the poor accessibility, but did not provide data on profits because they do not keep records.

|

Table 13. Use of some common local feedstuffs for pigs, % |

||||||||

|

|

Takeo |

Pursat |

||||||

|

Krom |

Sras trakun |

Takouk |

Mean |

Kra Gnao |

Chhung rouk |

Tasas |

Mean |

|

|

Rice bran |

||||||||

|

Yes |

66.7 |

77.8 |

66.7 |

70.4 |

88.9 |

88.9 |

100.0 |

92.6 |

|

No |

33.3 |

22.2 |

33.3 |

29.6 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

7.4 |

|

Broken rice |

||||||||

|

Yes |

44.4 |

22.2 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

11.1 |

44.4 |

29.6 |

|

No |

55.6 |

77.8 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

88.9 |

55.6 |

70.7 |

|

Rice meal |

||||||||

|

Yes |

22.2 |

22.2 |

22.2 |

22.2 |

33.3 |

44.4 |

55.6 |

44.4 |

|

No |

77.8 |

77.8 |

77.8 |

77.8 |

66.7 |

55.6 |

44.4 |

55.6 |

|

Kitchen waste |

||||||||

|

Yes |

44.4 |

33.3 |

44.4 |

40.7 |

44.4 |

77.8 |

55.6 |

59.3 |

|

No |

55.6 |

66.7 |

55.6 |

59.3 |

55.6 |

22.2 |

44.4 |

40.7 |

|

Water spinach |

||||||||

|

Yes |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

77.8 |

88.9 |

77.8 |

|

No |

33.3 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

33.3 |

22.2 |

11.1 |

22.2 |

|

Concentrate feed |

||||||||

|

Yes |

0.0 |

11.1 |

0.0 |

3.7 |

33.3 |

44.4 |

66.7 |

48.1 |

|

No |

100.0 |

88.9 |

100.0 |

96.3 |

66.7 |

55.6 |

33.3 |

51.9 |

Discussion

Taro is a wet land crop that is cultivated in most regions in Cambodia. There are two kinds of taro, the water taro and land taro. This survey is agreement with Florida ID: (899) that reported that Taro falls into two main groups: Wetland taros and upland taros. Taro is a tropical plant grown primarily as a vegetable food for its edible corm, and secondarily as a leaf vegetable. Its flowers are also eaten. The Chouk and Sla taro varieties can be considered as "taro cocoyam" or "old cocoyam". Its scientific name is "Colocasia esculenta" and the binomial name is "Colocasia esculenta (L) Schott" (Wikipedia 2006).

The Chouk and Sla taro varieties are quite similar in DM and CP (Table 4), but these values are higher than the values of FAO (1993) for Colocasia esculenta, and also higher than the values for Xanthosoma reported by Baruah (2002), Leterme et al (2005), Agwunobi et al (2004) and Rodriguez et al (2006). However, these differences can be the result of differences in fertilizer application, age of plant, and sampling procedure.

The two varieties are short term varieties (6-8 months), which are suited to the climate of Cambodia, with two main seasons, a six months dry and six months rainy season. Farmers can start planting in the late dry season and early rainy season, from April to July and can harvest from December to January. During harvesting, which is in the dry season, farmers stop applying water and then collect the tubers for sale and home consumption. The tuber yield was found to be different between locations due to differences in the management and fertilization. The average tuber yield was 4.5-6 tonnes ha-1 for all sites, which is lower than the results of Salam et al (2003), who reported that the highest biomass yield of corms was 7.20 tonnes ha-1, while Susan et al (2003) reported that the total biomass yield of corms ranged from 7.64 to 9.25 tonnes ha-1. The average yield of stem and leaf reported by the interviewed farmers was 5.0-8.5 tonnes ha-1. The low yield of stem and leaf may be an effect of the way of estimating yield, because farmers weighed only 1m2 of stem and leaf, and then using this value calculated yield for the whole area of their lands. However, it was not only very difficult to separate petiole and leaf yields but also very difficult to get reliable whole petiole and leaves yield, because it would be affected by harvesting method.

The use of taro for pigs is not widespread, because farmers lack the knowledge of how to use and process of taro, and also of the benefits of taro for pigs. However, 96% of farmers fed taro to their pigs after boiling with broken rice. Sometimes they observed that the pigs still had a problem with itching, but not as severe as after feeding fresh taro. This point was also made by Miller (1929), who said that the stems are peeled and boiled before being fed to livestock, particularly pigs. Boiling is the most suitable method for the farmers in Cambodia, because in practice they always boil all feeds before giving them to their pigs, and also because they are worried about itching. However the growth performance of pig that fed the boiled petiole and leaves with broken rice are seemed to be better, but there are no data on this. Agwunobi et al (2002) reported that boiling reduced (p<0.05) the amounts of the antinutritional factors in taro cocoyam cormels, and that feed intake, weight gain and feed efficiency for the diets containing boiled taro cocoyam cormels were better than for non-boiling and sun-drying.

Conclusions

-

Two varieties of taro, Chouk and Sla, are commonly cultivated, and Trav Prey (wild taro) grows naturally in Pursat and Takeo provinces. Chouk and Sla taro are short-term varieties and can be harvested 5-8 months after planting. Taro is considered to be a good vegetable crop that is planted nearby the houses in the two selected provinces of Cambodia.

-

Tubers of taro are used for human consumption, while stems and leaves are not widely used for animal feeding. The main reasons for not using them are itching, and lack of knowledge.

-

The average tuber yield was 4.5-6 tonnes ha-1 for all sites, and the average petiole and leaf yield reported by interviewed farmers was 5.0-8.5 tonnes ha-1

-

Farmers considered stems to be most likely to cause itching, followed by leaves then root. However the effect can be reduced by boiling, frying, ensiling and sun-drying. Both salt and sugar palm syrup can be used for ensiling.

Acknowledgments

The present survey is part of a study on ensiled taro (Colocasia esculenta) leaves in diets of local crossbred pigs in Cambodia, supported by the MEKARN project, financed by Sida-SAREC. The authors express their gratitude to the PRA team of CelAgrid for help in collecting the data, and also thank the authorities and farmers in Pursat and Takeo provinces who spent time with the team during the interviews.

References

Agwunobi L N, Angwukam P O, Cora O O and Isika M A 2004 Study on the use of Colocasi esculenta (Taro cocoyam) in the diets of weaned pigs. Tropical Animal Health and Production 34: 241-247 http://www.springerlink.com/content/wxknvypgpc97b419/?p

AFRIS 2004 Animal Feed Resources Information Systems. Updated from B Göhl, (1981) Tropical feeds. Food and Agriculture Organization http://www.fao.org./ag/AGa/agap/FRG/AFRIS/DATA/535.htm

Baruah K K 2002 Nutritional Status of livestock in Assam. Agriculture in Assam. Publ. Directorate of Extension, Assam Agric. Univ. Pp : 203

FAO 1993 Tropical Feeds by B. Göhl. Computerized version 4.0 edited by A Speedy, Rome, Italy

Florida I D: 899 Colocasia esculenta http://www.floridata.com/ref/c/colo_esc.cfm

Leterme P, Angela M L, Estrada F, Wolfgang B S and Buldgen A 2005 Chemical composition, nutritive value and voluntary intake of tropical tree forage and cocoyam in pigs. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 85: 1725-1732 www.bsas.org.uk/Publications/Animal_Science/2006/Volume_82_Part_2/175/pdf

Miller C D 1929 Food Values of Breadfruit, Taro Leaves, Coconut and Sugar Cane. Bernice P. Bishop Museum. Bulletin 64. Honolulu, Hawaii

Rodríguez L, Peniche I and Preston T R 2006 Digestibility and nitrogen balance in growing pigs fed a diet of sugar cane juice and fresh leaves of New Cocoyam

(Xanthosoma sagittifolium) as partial or complete replacement for soybean protein. Workshop-seminar "Forages for Pigs and Rabbits" MEKARN-CelAgrid, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 22-24 August, 2006. Article # 15. Retrieved February 8 (107) from http://www.mekarn.org/proprf/rodr2.htm

Salam M A, Patwary M M A, Rahman M M, Hossain M D and Saifullah M 2003 Profitability of Mukhi kchu (Colocasia esculenta) production as influenced by different doses and time of application of urea and muriate of potash. Asian Journal of Plant Sciences 2 (2): 233-236. ISSN 1682-3947

Susan C, Miyasaka R M, Ogoshi G Y, Tsuji L and Kodani S 2003 Site and planting date effects on Taro growth: comparison with Ariod model prediction. Agronomy Journal 95:545-557

Wikipedia 2006 Taro, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taro